Hadley in Silent Film

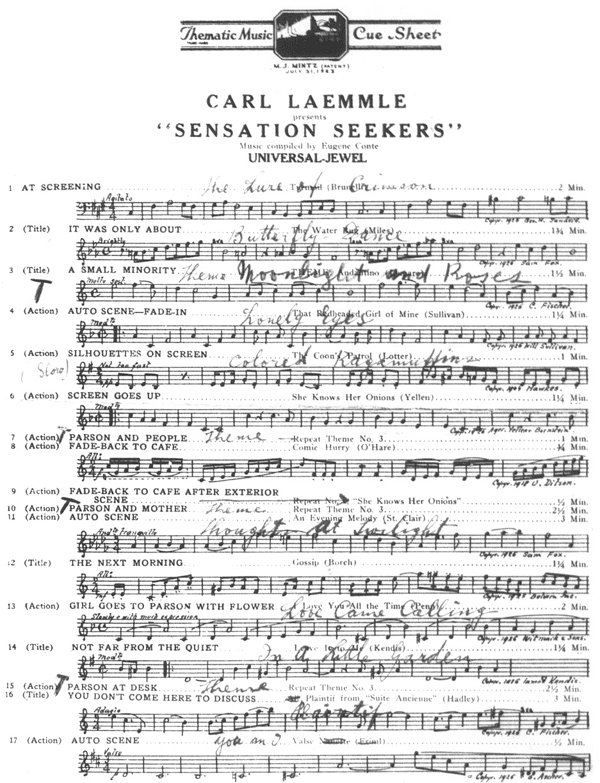

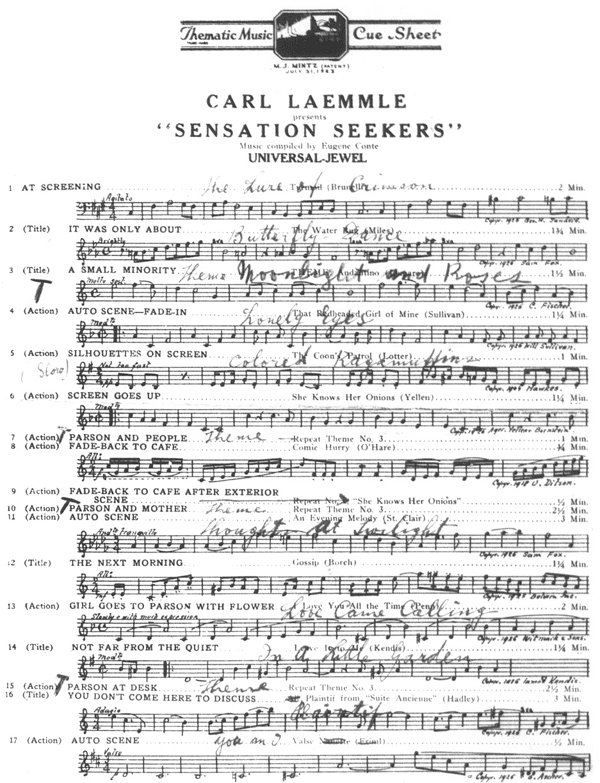

Cue sheet for Sensation Seekers, 1927. Hadley's "Plaintiff" from his Suite Ancienne, Op. 108 is called for as cue#16, a title, approximately twenty-three minutes into the film. Depending on the venue, this might be played by an orchestra, a tiny ensemble, a pipe organ or a piano. Copyright is ascribed to Carl Fischer, with the first eight bars prompted on the sheet. Parts could be obtained either from the sheet publisher, or pulled from the extensive libraries that large theaters maintained. Suite Ancienne was originally published as chamber music for accompanied violin, cello, or piano solo. Throughout the silent film era, such composite accompaniments from a stock library were one of the most common methods of providing uninterrupted music for the film. Completely improvised accompaniments from a solo keyboard, utilizing the same sort of themes was also common, along with fully written-out, original scores. The desire for a consistent musical accompaniment to a film with no spoken dialog was one of the major motivations driving the development of recorded soundtracks. (special thanks to silent film performer Frederick Hodges for assistance in locating this example.)

"Silent film" was never silent, of course, in a theater showing. The precise details of Hadley's early involvement in film music are not known, but many clues suggest that an early beginning is possible. As a young composer on the New York scene before 1900 he was busy ghost-writing melodies for musical theater as well taking a hand at publishing popular sheet music alongside his more serious classical endeavors. He began recording short compositions in the years before World War One. Ever guided by his mentor and friend Victor Herbert, he would surely have followed Herbert's lead by 1915 (Death of a Nation, extended musical accompanyment ) if not before. Melodic compositions ranging from popular marches, Bohemian Grove musical plays, short chamber works of a salon nature, opera preludes and arias, and concert themes such as the tremendously popular "Angelus" extracted from the Third Symphony all made fine film and theater cue material.

No discussion of Hadley and film music is complete without including Herman Heller. European-born and trained, Heller was already an established cafe, theater, and occasional concert conductor when Hadley engaged him as a violinist in the new San Francisco Symphony in 1911, coinciding with the early development of the feature film in the United States. It may be difficult to say who influenced whom. Clearly a relationship of mutual friendship and assistance developed over more than fifteen years, as both were involved in developing amplification, broadcast, and recording. As director of the Warner Theater in New York, then music director for Warner/Vitaphone, Heller was involved in Hadley's conducting of the landmark 1926 recorded-sountrack Don Juan, and was personally responsible for engaging Hadley in composing his timeless, recorded score for the non-dialog 1927 When A Man Loves (Manon Lescaut).

Hadley, ever prolific, produced a great deal of music that has not been cataloged. However, his catalog as published after his death does list several non-opus pieces specifically for film, with evocative titles such as Battle of the Centaurs, Blue Butterflies, Coquette, Buffoons, Dance of the Satyrs, and East Wind. Some idea of his uncredited, recorded film contributions is listed in his IMDB filmography.

Examples of Hadley's cue music as it was once presented can be heard in recordings today by Frederick Hodges and Rodney Sauer, among others.

Hadley was, if not the inventor, a pioneer in what today we might describe today as "classical music videos" - using live accompaniment, of course. This aspect of Hadley's cinematic experimentation took place around 1918 and was described at the time as follows:

Hopp Hadley has been at work on a musical scheme which will come as a novelty upon some of our musical directors. He is combining music with pictures in such a way that one completes the other. For material he has gone to the various song cycles, which are usually composed in sequence style, giving an almost complete story in four or five songs. Sullivan's "Lost Chord" was his first production, and his latest effort is the "Eliland" of Von Fielitz. Mr Hadley has renamed the cycle. He says:

"The first Cinema-song cycle is 'The Vow'. The song cycle 'Eliland', which it illustrates, is too well known to need any introduction... The picture is practicable from the theatre standpoint in every way, although, of course, it is only suitable for first class houses.. It runs just thirty minutes, and will be offered as a novelty for theatres featuring their music, and also for use as a concert number. I believe that it will mark the introduction of motion pictures into the concert world. (Montiville Morris Hansford, "Picture Accompaniment", Dramatic Mirror, Nov. 1918 as quoted by Canfield, p.164).

It would seem from this description that Hadley created orchestrated versions of these song cycles, and film was created to match them, so that the film was created to go with pre-existing composition - a radical experiment decades ahead of its time.

Library of Congress