When a Man Loves - “WAML” for simplicity’s sake - a non-dialog movie with a synchronized musical soundtrack, is a movie and score that is waiting to find its full place in film, film music, and general musical history. While it has long been recognized as the first feature length film of its type with a fully-composed, recorded and synchronized soundtrack, it has been overshadowed by the exuberant first Vitaphone synchronized sound feature, Don Juan, and the well-known Jazz Singer with Al Jolson which shortly followed WAML and launched spoken dialog into the movies. Often it is discussed in the context of only one or two of its several areas of significance.

In assessing WAML It is helpful to consider all of these areas: the history of the Manon story including its many representations on stage and screen, the development and state of film music in 1927, the introduction of sound technology including Hadley’s involvement in its introduction, the merits of the music apart from the film, the production values of the film apart from the music, and the lives and personalities of Manon’s original author Abbe Prevost, the two leading stars John Barrymore and Dolores Costello, and Hadley himself.

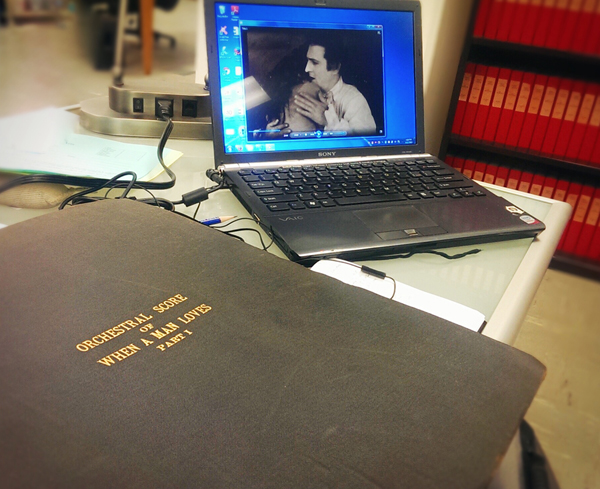

We are very fortunate in that a good copy of the 1927 recording, which was done on 33 1/3 rpm, hard shellac disks, miraculously survived and was rediscovered with a large set of Vitaphone disks on a Warner back stage in the 1980s. The film was brought back from more than one source for restoration, mostly in full size prints, and is now available to be seen and heard on DVD through Warner Archives. As it becomes better known and studied it is to be hoped that someday the music, remarkable for its time and still very compelling today, will get live performances with and without the film, and will receive the new recording in full fidelity that it so richly deserves.

Manon Lecaut is one of the great classics of French literature. Written by Abbe Prevost in 1731 as the seventh volume of his Adventures of a Gentleman of Quality, The History of the noble des Grieux and of Manon Lescaut was an immediate success - quickly banned, eventually revised to create a more moral tale, and adapted into several works for the stage. There are not just the two best known operas by Puccini and Massenet, but also an earlier, brilliant one by Daniel Auber, still in the repertoire today, and the more recent jazz-influenced lyric drama Boulevard Solitude by the concert composer Hans Werner Henze. It was also the subject a famous ballet that had great influence on the Paris tradition, and was the subject of other movies before and since, including another 1926 silent film. The number of translations, printings, editions, and scholarly dissertations is beyond accounting, and it is safe to say that Manon makes a very great number of appearances on stage, and in classroom assignments and discussions each year. Each new creation joins very heady company, and Warner Bros. went to great lengths to make theirs a worthy addition. Fine actors and actresses were used throughout. Filming was done on lavish, detailed sets depicting French country life, the streets of Paris, the opulence of Louis XV’s court, a beautiful church, grim prison and dockside scenes, authentic ship interiors, and so forth. An artistic program with an embossed cover, available at showings, explained that Louis XV courtly costumes were borrowed from the French National Archives under a $25,000 bond, (over $300,000 in 2013 value), to help assure authenticity.

The great stage actor John Barrymore, star of many films, was given the role of the young gentleman des Grieux, and the dramatic story line, which in stage productions is normally centered around the young beauty Manon, emphasizes his story as is the case in the novel. He chose one of the radiant beauties of the film world, Dolores Costello, out of personal interest, but Costello was an ideal choice to portray the naiveté and simple compulsiveness of the highly contested Manon. As Barrymore was given the highest billing and leads much of the drama, the story was somewhat more a “des Grieux” and as such has lent its ultimate title to several succeeding films. The plot develops quickly but allows for steadily deepening levels of involvement and contrast, culminating in great physical action far removed from the simpler life where the story begins.

Music was very important aspect of silent film performance from its beginning, provided by piano, organ, and orchestra. There were several important approaches taken, but when properly done - not always the case - most emphasized a system of short motifs and medium length musical settings strung together or played appropriately to help set particular moods. The music could be very fine - the French composer Saint-Saens is credited with an important, eighteen minute film composition in 1908, Victor Herbert provided a much longer set of music for Fall of A Nation in 1916, and other noteworthy composers, not as well known today, provided music representing the latest classical innovations. Film music could also emphasize popular and familiar melodies, pure improvisation, and whatever music was available or known to the performer. For movies where the score was not written out, the concept of cue sheets along with classification of musical motifs as to suitability for certain types of scenes, allowed the use of large libraries of established music. The concepts of compiled musical scores of was not new at all to the movies, having been used in principle for hundreds of years in street productions, puppet operas, and the like. Large theaters, which were also producing vaudeville, might have many thousands of short pieces ready for use. When the distribution of recorded soundtracks was considered, spoken word was not a consideration; rather, the goal was a fine and consistent musical performance to eventually accompany the films wherever they were shown. Although film sound technology had been under development for several years, the rapid growth of radio helped spur its introduction into commercial release. “Sound on film”, as we are accustomed it today, where the soundtrack exists next to the picture on the film (and now appearing on digital media), was being developed, but Warner Brothers chose a technology that used record disks, superior to sound on film at the time. This also gave Warner licensing advantages but still resulted in a system with limited dynamic range and always presented synchronization challenges. Female voices and higher wind instruments were particularly affected, a topic that has been discussed by numerous authors.

Hadley was involved in film music for at least a decade and half prior to the first Vitaphone release. Music from his operas, symphonies, and stage musicals, including his two Bohemian Grove productions (a third would follow) were a part of the standard literature that was incorporated into compiled or improvised film scores and productions. He also produced specific genre pieces for use in this way. He was involved in early musical sound technology, apparently consulting and certainly conducting on the first broadcast of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1924. Warner’s first Vitaphone release featured a short film of Hadley conducting the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in Wagner’s Tannhauser Overture, and Hadley conducted the orchestra for its full length feature, Don Juan. For the second Vitaphone release, a comedy set in the battle areas of World War One titled The Better ‘Ole, Hadley created a compelling and appropriate composite score consisting of a mix of existing and new material, in the silent film tradition. For the early Vitaphone releases, it was necessary to create films that could be shown without the soundtrack, and the regular silent release schedule was proceeding in any event. Future authors - hopefully soon - will reveal more of the story, but Mrs. Hadley recounted in the 1940s how the conductor of the Vitaphone Orchestra, Herman Heller, came personally to Hadley’s apartment in New York to ask him to compose a Manon Score. What a compelling challenge this must have been for a composer of operas and symphonies, so aware of the Manon legacy and the inevitable comparisons. Yet Hadley must have been aware that it was in Warners' vaults; it is interesting to speculate that he may have been saving up some thematic material.

There is much that sets Hadley’s score apart from the majority of the film music of the time. Actually, it falls into a very narrow class of its own simply due to the shortness of the period when soundtracks were recorded without dialog and were heard continuously through the movie. A keyboard player has great latitude in keeping in step with a film, but it is very difficult for an orchestra, and the larger the orchestra, the less flexibility in getting back into place once things have slipped out. Operas with continuous music (such as Wagner’s) have recourse on stage that is not possible with film. Thus for film, with even a moderately large orchestra it is often easier to play in sections that can be started at appropriate times and finish in time for the next one. Movies with dialog also follow this pattern. Compositionally, though, Hadley the advantage of writing for a situation where the music could be continuous, as the timing would be fixed, allowing for the largest possible overall structures and development. Well versed in the opera tradition, he wrote in a fluid, lyrical style that allowed the large orchestra to play continually as in a Wagner creation or as silent movie keyboardist would do. While interesting to note, this does not create a compelling listening experience in itself. But Hadley’s score is at once both melodic and mood-setting. The melodies are not the sort that one would sing but represent a Wagnerian technique known as leitmotif, or “leading motive”. These are recognizable musical fragments representing a character, place, or situation, that can be fitted together, while being constantly altered to fit the moment as they help draw the listener into the personality of the character portrayed. Hadley’s great skill in constantly varying and weaving his themes together, changing the orchestration, altering the mood via major and minor keys, and adjusting tempos, keeps the music fresh and interesting. But what really stands out, especially in a Hollywood film of 1927, is the broad, arching, deeply romantic canvas that he paints. Much of the European film composition done elsewhere at this time represents the best of modernist Classical trends, and these compositions are still important today. But Hadley’s music anticipates the grand, elegant sweep and sound of the great films of Hollywood’s Golden 1930s - five to ten years before many of the most celebrated scores written by the group of expatriate Europeans, and some Americans, that dominated that wonderful decade.

Other compositional techniques that are not obvious enhance the cohesiveness of the score. In serious concert writing, very short melodic fragments are often the basis for long pieces of work, as they are expanded greatly, written in different directions, turned around and upside down, and show their full melodic potential. (Think of the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, where the ominous first four notes are put to use over and over again, across all four movements, in dazzling variety). Hadley uses a short scale passage, sometimes directly in scale order, sometimes with small intervals or jumps, sometimes with a rhythmic enhancement, as the kernel of several different melodies, lending a unity and consistent feel to the work. There are also sophisticated, interesting musical techniques such as his use of fugue, where a melody is stated on top of itself, re-entering in a new voice. This is often used for music of a high, noble, and intellectual nature and is used - in short amounts appropriate for an audience being entertained by a movie - to suggest the antiquity, dignity and grandeur of the French Court. Hadley was capable of creating complex, challenging compositions for the concert hall, but his long experience in writing for widely varying audiences and purposes is shown in his transparent handling of these musical disciplines. The large orchestra allowed Hadley to use his highly developed orchestration skills - something praised by the famous German composer Richard Strauss (Canfield p.80) - to create additional color and interest. Sprightly, integrated horn calls portraying screen action, glissandos in the violins to enhance the appeal of Manon's kitten, and the delightful appearance of saxophones to help suggest the luxurious decadence of the court, are enjoyable, lightly used touches. In 1927 these old techniques helped emphasize the new integrated sound while perfectly serving the musical line, and still charm today. WAML’s musical score plays at times like a tone poem for the concert stage, at others like a ballet with it its quick changes to follow the dramatic line, to a degree rarely if ever achieved by a film accompaniment up to this time. Whether this represents a revelation that affected expectations for the future is difficult to say. WAML was of necessity probably heard more often in its day without soundtrack than with it - but it can be safely assumed that it was sought out and examined by many leading film producers and composers of the day. And it was greatly appreciated by Hadley followers. His earliest biographer, Herbert Boardman, declared that it contained some of Hadley’s most beautiful music, high praise indeed for a composer whose compositions had graced concert stages all over Europe and America, and whose operas saw success at the Metropolitan in New York and in Chicago.

The full story of des Grieux and Manon Lescaut is not normally presented in drama, it is shortened and adapted for the audience, and WAML is no exception. It is faithful in spirit to the original - up to a certain point anyway. Long-time Manon enthusiasts watching WAML for the first time should be prepared to enjoy it with artistic tolerance and not be disappointed if some favorite scenes and even whole sections give way for Hollywood considerations. But there are features of the story and this particular production that give special meaning to what some might dismiss as a simple costume contrivance, no matter how beloved. Several autobiographical and participatory elements In WAML give it a delicious authenticity. Abbe Prevost’s own story is more fascinating than fiction; without giving too much of the story away perhaps it is enough to say that Prevost apparently had the aspirations that des Grieux does early in the story and succumbed in the same way, settling permanently into a full calling only later and using the material as a true basis for his Adventures. Two centuries later on the set of WAML John Barrymore was pursuing Delores Costello, and a true romance developed as the filming unfolded; the passion on the screen is very real. They were to marry, and one grandchild, Drew Barrymore, is well known to us today. And Hadley, by his own word, had been intrigued by Manon Lecaut from his boyhood days¹. But the dignified Henry Hadley also had an early bohemian period in Paris that he always remembered fondly, and one would like to think that he composed music about youth in Paris directly from the heart, and from personal observation.

There is more that has, can, and should be written about WAML - outstanding direction by Alan Crosland, great performances by the supporting cast, including Warner Oland of later Charlie Chan fame as Manon’s deliciously scheming brother, an uncredited appearance by Myrna Loy. There is much irony also. It was overpowered by later movies, hampered by the limitations of its recording technology, even parodied, perhaps, in movies referencing the silent era. Despite the great exposure afforded by being a Vitaphone star, the technology, so problematic to speaking roles, was ultimately damaging to Delores Costello’s career. She stands as a pioneer of the truest sort in that regard. John Barrymore and Henry Hadley both drove themselves very hard in very different ways; each would pass away within a decade of WAML’s time of brief glory, when it was featured on the cover of the New York Times’ magazine section, and delighted moviegoers swore that they forgot that they were listening to recorded sound. Modern technology has added to the miracles of the nineteen twenties, allowing us to hear the original recording repeatedly and enjoy discovering its delightful surprises. Hopefully someday a suite of WAML’s sparkling and haunting melodies will become known to concert audiences, and silent film audiences will be treated to the choice of the original Vitaphone experience or a new, stereophonic, high fidelity soundtrack. Rare complete live performances will be treasured by anyone lucky enough to witness them and experience a truly remarkable marriage of film and musical sound.

Coming: Illustrations, sound and video clips

Appreciating When a Man Loves / Manon Lescaut (1926-7)

USC Warner Bros. Archives